In honor of Women’s History Month, I thought I would share what I’ve found.

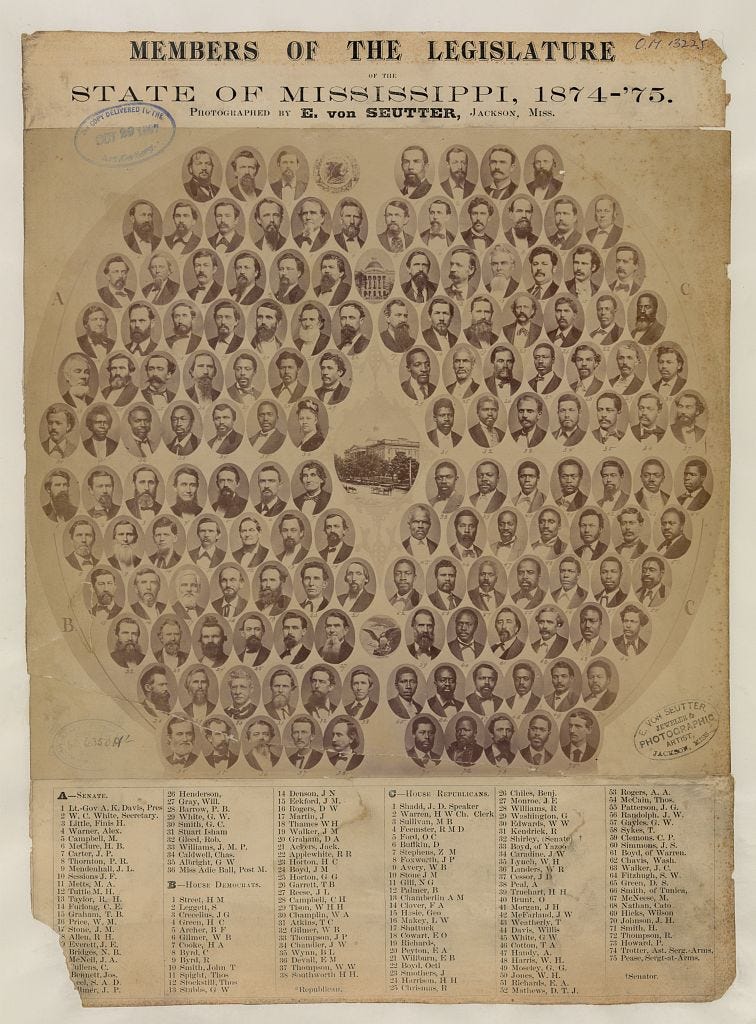

Over the years while I’ve been researching the Vicksburg Massacre for my novel, I would come across the Members of The Legislature of the State of Mississippi, 1874-75 picture.

The image that I would see on the internet would be a little blurry, but I still marveled at how many Black men I saw in the photo and wished I had known about them and others when I was in school.

Earlier this year, I decided to download this image from the Library of Congress which was much clearer and this time I made a point of looking at each photo. And to my surprise I saw a WOMAN.

I couldn’t believe my eyes.

I wondered who is she? What is she doing there? She couldn’t have been an elected official. Women weren’t even allowed to vote, yet. I tried to figure out which name was hers in this list but that was hard to tell, because the numbers are very faint.

So, I searched and searched but came up with nothing.

Until I was researching something else regarding the Vicksburg Massacre and normally when I’m researching on the internet, I tend to go down rabbit holes. One website, lead me to another website and so forth.

I landed on this website Against All Odds. The first Black legislators in Mississippi. Website created by DeeDee Baldwin, a history research librarian at Mississippi State University.

I clicked around and to my shock and amazement, there was a page labeled “Who’s That Woman?”

And it had her picture.

And her name… Adie Ball. And what her position was… Postmistress.

I screamed in delight!

Not only was I happy about finding out her name and occupation, but just thrilled in general because during my research I haven’t been coming across many stories of women of color for the time period 1873-1875 in Mississippi. These are the years where my novel takes place and I really wanted to include some notable Black women.

So, what does a Postmaster or Postmistress do?

According to the NGS Newsmagazine, during the 19th Century, “Some postmasters served only a few months, while others served for decades. Most were men; some were women. It was a political appointment and a position of trust. The postmaster handled money; other federal agencies counted upon the postmaster for honest opinions.”

Then I later read in the Smithsonian National Postal Museum…

“Since the 1800s, the Post Office Department successfully employed postmasters and women entered the twentieth century with nearly ten percent of existing postmaster positions. (Postmaster General George) Cortelyou claimed that the Post Office was the largest and fairest employer of women, “with the exception of the public-school system.” He boasted (inaccurately) that the Department paid the same salaries to both men and women.

The Post Office Department was not as hospitable to women as Cortelyou presented it to be. Just four years earlier in 1902, The New York Times reported that many civil service employers (including the Post Office) requested only names from the male register. Even though more women took and passed the exam, this system kept many women from being hired. An official defended this policy as being beneficial for everyone involved:

“Every time a woman is appointed to a clerkship in one of the departments she lessens the chances of marriage for herself and deprives some worthy man of the chance to take unto himself and raise a family. And in addition to that the men make far better clerks, They complain less, do more work, and work overtime if need be without grumbling.”

Marriage could be an issue for female postal employees. In the early 1900s, Postmaster General Henry Payne did not approve of married women working because he believed that they should be supported by their husbands. In 1902, Payne ordered that, “a classified woman employee in the postal service who shall change her name by marriage will not be reappointed.” In certain post offices, female clerks already employed in the Post Office were required to “send in a written statement setting forth whether she is married or single, the name of her husband, if she has one, and his occupation.” These orders discouraged married women from finding employment in the post office and single female employees from marrying if they wanted to keep their jobs. Rather than finding a job in the post office that would keep women “in contact with the home and family,” Payne advocated that married woman “stay at home and attend to their household duties.” Payne also cited financial influences behind his decision. Since it was possible that a woman could marry another government employee, the government could potentially pay a single family two salaries. He believed it was “enough for the government to pay a salary to one member of a family.”

Those last paragraphs are highly loaded with so many inequalities that it makes my brain want to explode. Even more reason to honor women like them that came before us. To think about the mentality back then blows my mind.

But anyway, getting back to Adie Ball. There’s not much that DeeDee Baldwin has found on her background, and I haven’t either. If you have any information, please contact me or Baldwin via her website.

Baldwin does mention two other Black women that were postmistresses. Miss J. M. Lynch, the sister of James D. Lynch. She was appointed postmistress of Beaufort, South Carolina.

James D. Lynch was the Secretary of State of Mississippi from 1869-1872

Baldwin also mentions Minnie Geddings Cox who was appointed postmistress of Sunflower County in Mississippi by President William McKinley in 1897.

There’s definitely a lot of information about Minnie Geddings Cox and some about Miss Lynch. I would like to dive in more about them as well, but at another time.

But for now, I just wanted to share my excitement about finding info about Adie Ball. It’s really thrilling to stumble upon her information, and I hope with this platform, I will get to learn more.

Thank you for reading and have a great day!

Danita

Fascinating story.